8

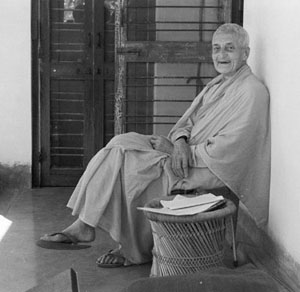

Brahmacharini Atmananda

Sri

Anandamayi Ma Ashram

Rajpur

Dehra Dun

27th December 1980

I am now packed ready to leave. I have the travellers cheques. I have 50 audio cassettes bulging out of all pockets. I listen to Kate’s last words of advice, and the tape recorder and its extention are off. The distant Himalayan snows are shining: by the time I see them again they will be veiled in purdah. As I reach the road a tourist taxi (in late December?) passes: I am given a lift down to the Mussoorie bus station which saves me an hour’s walk — an auspicious sign.

The bus is taking me to Rajpur where I used to live,

and where I have to find Atmananda who has half-promised to try and give her

blank-recorded-Interview again.

But first I call at the Sakya Monastery. The place is empty. I am told H.H.

Sakya Trizin is away. No chance of getting an Interview from a Western Buddhist

here. But I do meet Shyam Bodhisattva: he writes on the back of an envelope

the name of a friend at the Rajneesh Ashram in Poona. If you go there —

he says, all encouraging smiles — Leela, she is the press officer, will

be the best person to help you, and you will find that place -- well -- interesting.

But for now I am walking through the nearby sleepy

gardens of the Anandamayi Ma Ashram on Rajpur Road. Atmananda, whose earlier

Interview atempt registered nothing but recorded silence, is sitting in the

porch of her tiny house; she appears to be surprised:

I wrote to you — she is saying — telling you not to come before

3 o’clock!

Oh, Lord, another mistake! But I explain: The banks don’t issue travellers cheques over Christmas, so perhaps the post office only delivers Christmas cards, and can’t be bothered with letters during this period.

She lets me in, but she is firm: I will not speak into that thing again...here is a printed article...(not another one?)…use that instead!

I glance at it. There are places needing clarification. She starts explaining, talking so expressively, so much more naturally, I put the printed, stilted piece aside. She lets me press the recording button -- this time something surely will be captured.

Interview 8

When I met you last month at Kankhal, you were

reluctant to give me an Interview — you said you didn’t want any

personal publicity. When at last you agreed, we found much to your amusement,

nothing had been caught on the cassette. I know you have lived in India for

nearly 50 years and that you are one of Anandamayi Ma’s oldest and first

Western disciples. But can you tell me something about your early life and what

brought you to India?

My mother died when I was 2 years old so I was brought up by my father and grandmother.

He was Polish, but we lived in Vienna. I was interested in religion very early,

but I went through many phases. At school I learned about the Jewish religion,

and I got very Jewish. I remember saying to my grandmother: I can’t stay

here, you don’t keep orthodox rules — I’m going away! All

right — she said — but where will you go? I was 7, so I began to

think I better wait.

But by the time I was ten I was an atheist. When the First World War started, I got interested in politics — this lasted a year or two. But I was still religious-minded and began to read Tolstoy when I was 14. That impressed me very much.

When I arrived at the age of 16 I became a vegetarian and started reading Theosophy. But, really, it’s very difficult to talk if you are going to publish everything.

Yes, I know. But only

what you wish to talk about will be published. You know, our backgrounds are

rather similar: I was also born a Jew of Austrian-Polish parents, and like you

I became a musician. Can you tell me how you started your musical training?

It was while still a child of 6 or 7. I was considered a wunderkind, although

I successfully avoided playing in public. It was at my music teacher’s

that I met a girl, much older than I, who was a Theosophist. She gave me some

books to read, but I didn’t like them. Then she brought me Krishnamurti’s

little book At the Feet of the Master. I didn’t read it. After some time

she wanted it back, so I felt I better read it — you probably know it

— it’s very short. Well, it had a peculiar affect on me. From that

day I couldn’t eat meat anymore. My family thought I’d get over

it, but since then — it’s over sixty years ago — I have never

eaten meat. It became contagious: my sister became a vegetarian after one year,

then my father, and as my grandmother had no choice, she also followed. It was

like that.

From then on I became a keen Theosophist. When I was 21 I came to India for the Jubilee Convention at the International Headquarters in Adyar. That was in 1925. Dr. Annie Besant and Mr. Leadbeater were alive in those days. I should tell you that I had been fascinated by India since my childhood although I didn’t know anything about India. When I first heard the names of India’s two great epics: Mahabharata and Ramayana, I went home from school repeating those words like a mantra. Of course, I didn’t know what a mantra was until much later.

When did you come back

to India?

Oh, it wasn’t for another ten years… in 1935.

And this time you never

went back?

I have not even stepped outside India since then.

How did you meet Anandamayi

Ma? She could hardly have been so well-known in those days.

I was teaching at Rajghat School in Varanasi, and although I had heard much

about Mataji from friends who knew her, and I was

searching for spiritual guidance, I was in no hurry to meet her. It wasn’t

until 1943 when I was spending my summer vacation in Almora that I had my first

darshan. The Danish sadhu

who lives there one day said to me: “The Holy Mother is at Patal Devi, why don’t you see her on your

way back?” The Ashram there was not built then, but I found Mataji sitting in the open on a string cot.

A few devotees were squatting at her feet. She seemed all joy and beauty. She

addressed a few words to me. She didn’t treat me as a stranger but as

if I were well-known to her. At that time I knew no Bengali and only some colloquial

Hindi, not enough for a serious conversation. I wanted to know more about her.

In those days there were no books on her in English. She was always travelling,

never in one place for long.

All my life I had been taught to look at things critically and never accept anything on authority. I knew it was difficult to distinguish between an enlightened being and one with a semblance of this divine state. At that first meeting I was wearing European dress, a solar topi, I carried a hand-bag in one hand and a mountaineering stick in the other. My appearance clashed painfully with Mataji’s surroundings, and I was sensitive to the curious glances of the devotees.

Nevertheless, I was struck by the inward beauty that shone from their faces. After 15 minutes I got up to go, but within a few months I was able to have Mataji’s darshan in Varanasi, where I taught.

This time she was surrounded by a huge crowd under a pandal by the Ganges. This was the site chosen as her new Ashram, although no building had started. Kirtan was going on. I was not used to this spectacular worship and felt out of place.

In spite of the dense crowd and the loud singing and dancing which disturbed me, there was something about Mataji which attracted me profoundly. I wanted to know her at closer quarters, but the chance didn’t come so quickly.

She says: No one can come to me until the time is right. It was, therefore, two years later before conditions brought me closer to her.

It was at Sarnath. I was allowed to spend a whole evening with her on the roof of the Birla Dharamsala. Here there were no crowds, only a few companions and Buddhist monks. It was informal and I didn’t feel out of place. Sarnath had been my favourite place of pilgrimage ever since I had come to Varanasi ten years before. I spent much time there reading Buddhist scriptures, enjoying the peace and wondering how it was that after millennia the presence of Lord Buddha could still be felt so strongly. I never dreamed that Sarnath, where he delivered his first sermon after attaining illumination, would be the setting for a decisive turning point in my life.

I sat quietly by Mataji not wanting to ask anything, just imbibing the atmosphere. Several days passed like this until one evening I had a long private talk with Mataji. What she said was so simple and convincing; no room for doubts. I thought: How strange I had not been able to find this out myself. And yet I knew it was not another talking to me, but my Self conversing with my self. What Mataji said was evidently only the outer expression of something that took place simultaneously at a deeper level.

The next morning we had another talk to clarify some details, during which Mataji asked whether I had to support anyone in my family. Several weeks later I received news of the death of my aged father, the only near relative I possessed. He had died a refugee in America three days after Mataji had talked to me at Sarnath. The time to make close contact with her came when all worldly ties had dissolved. With extraordinary ease and naturalness she had exploded my problem. Where there had been a constant dilemma, now there was a straight path.

Was it from that time

you started editing the magazine “Ananda Varta”?

The nominal editor I have been only for five or six years, but, yes, I have

been doing the work from the beginning. The chief editor, Dr. Gopinath Kaviraj(1)

, trained me — he was wonderful to me. Anything I couldn’t understand

he would explain for hours. I used to think: What a waste of time — if

he would only dictate the answer I would use it and finish with it. Only afterwards

when he was no longer available did I realize he had trained me to do everything

myself. The magazine started in the early fifties and is published quarterly.

In those early days I had such an intense desire to know what Mataji was saying that I spent all my spare

time studying Hindi.

In a year I was able to talk to her without help. No sooner had that happened than Mataji would often call me to translate for foreigners. I had a unique opportunity to witness many private Interviews which enabled me to get first-hand experience of the universality of Mataji’s teachings and how she modified them to suit each person’s nature, conditioning and needs.

When you were young you

were such an accomplished pianist. I wonder if you ever miss classical music

now?

Every day I do kirtan for one hour, and at every Ashram

function also. Of course, this is Indian music. In the beginning when I heard

this loud music I would sneak out — I couldn’t bear it as my ear

was finely attuned to Bach, Mozart and Beethoven. I think I once told you that

when I first came out to India I played piano recitals on the Indian Radio.

My favourite composer was Bach, but I also played Chopin, Schumann, Ravel, Debussy,

etc. Yes, I gave it all up, but it never was my life really. I was born into

another culture and background, but this was no new life that I entered when

I came here… you see, I didn’t belong to that life.

You would never go back

to the West?

No, no, no! No question. But suppose I were deported, I know there would be

a quiet place for me somewhere. Even in the West people are living high up in

the mountains with no electricity, no running water. One can live the simple

life anywhere. If you are meant to live this life, you will live it wherever

you are…but I don’t want to go back.

Have you taken Indian

nationality?

Long, long ago… in 1951. But I have to tell you a strange thing. I don’t

have a passport. When I was filling out all the forms, they said: You don’t

want to go out of India? I replied: No, what for? So they never gave me a passport…I

don’t suppose I can ever leave.

Are you really 76?

Yes. I ought to tell you what happened in 1945 when I wanted to spend the Divali

holidays with Mataji at Vindhyachal. The war was not yet

over, and being an enemy alien I couldn’t leave Varanasi without permission…there

was a permit one had to get. I had only just been drawn close to Mataji. So I was anxious that permission

be granted. Can you imagine my joy when told henceforth I was free to travel

without permission? Since 1939 all my movements had been restricted. As soon

as I was free of desire to go anywhere except to be near Mataji, I was suddenly free to go anywhere

I liked.

Can you remember something

of special interest from those early days spent with Mataji?

I can never forget the Kali puja

which was celebrated at Vindhyachal during that first visit in 1945. Mataji was present throughout the whole puja.

Her face changed continually: a drama appeared to be enacted on her features.

I cannot claim to know how a goddess looks, but she was so radiantly beautiful

and so young that night, it surely could not have been the countenance of a

human being.

When the puja was over, I didn’t feel sleepy in the least, but I went to my room to lie down. Someone knocked at the door calling my name. An asana — a small meditation rug — was handed to me with the message: Mataji sends you this. It was 4 a.m., the time one usually rises for meditation. How subtle — I thought — Mataji is presenting me with a reminder: this is no time to sleep but to sit in meditation! I went outside to thank her; she was still surrounded by people, but she said to me: You were cold sitting without an asana? This small treasure is still with me although through the years it has become badly worn.

When I Interviewed Simonetta,

she had much to say about Ashram hells. Have you gone through any hells?

Now you see my place…where are the hells? Yes, in the beginning there

are difficulties, but difficulties are a necessary part of the training. People

from the West think that when you come to the guru you just bask in the Holy Presence.

That’s part of it — the other part is the difficulties. Mataji is often asked about this. She says:

Whatever happens to you is due to past karma which has to be worked out. We

come to Ashrams from different social and cultural upbringing and have to mix

together. Naturally it’s going to cause upheavals. But we take it as part

of the polishing.

Perhaps we only see this

when the polishing is complete? What do you have to say about the benefits of

Ashram life?

The secluded life isn’t a thing you choose like going to a hotel. It has

to be meant for you. The benefits? I couldn’t live any other life. Where

would I go? I could never live with a family.

When did you start wearing

ochre robes?

You probably know Mataji doesn’t give sannyas

to Europeans. In 1962 when I had been with her for almost twenty years, she

asked someone in my presence whether he wanted to take sannyas;

he was not willing. I said: “Mataji, I can take it.” She replied:

“Achha?”(2)

So she gave me a robe with instructions how to dye it and that I should bathe

in the Ganges before wearing it. My name she gave at the very beginning.

Is that when you started

shaving your head?

Oh, that!…no, no, that’s a funny story. Mataji never told me to do that. A few years

ago I slightly injured my head; it became septic and troublesome. I asked the

doctor to shave the hair off, but he wouldn’t. The wound didn’t

heal so I did it myself. The wound healed but I like to keep my head shaved.

With all the literary

work you have been doing, does it not keep you away from Mataji?

I am now too old to travel with her all the time. It was different in the beginning

— I was with her very much, at times going to small villages where they

had never even heard of a bathroom. I often had to sleep in a storeroom —

on the floor — having arrived in the middle of the night. All that was

good; you see, everything depends on your attitude. Yes, there may be Ashram

hells, but there are two sides to everything. If you wish to be with such a

being like Mataji, you have to be prepared to go through

ups and downs. I have seen Rajas and Ranis putting up with conditions they hadn’t

met before. It’s hard, but look at how many Ranis come of their own accord

to the Samyam Saptah!

Is that the austerity

week Mataji holds every year?

Yes. The one that has just ended is the 32nd. They started in 1952. You see,

Mataji is extremely particular about one

thing: Without self-restraint nothing can be achieved. Mataji firmly maintains if we live soft,

indulgent lives, nothing can be achieved. She tells everybody there must be

self-discipline. She says that worldly pleasures lead to spiritual death. But

knowing that most people live like this these days, she started advising them

to keep one day a week or at least one day a month to observe strict rules:

eat only one meal, don’t smoke, drink or talk unnecessarily, don’t

visit anyone but stay at home reading scriptures and meditating.

What were the eating

arrangements during this week?

On the first day we only take Gangajal — water from the Ganges. The next

six days, nothing until mid-day when a simple meal is served. We are not supposed

to take tea or coffee but as much Gangajal as we like. That is most cleansing.

In the evening there is hot milk for those needing it.

Why do you drink so much

Gangajal?

According to what the stomach consumes so will the mind work. When we start

this austerity week, the first thing to be done is to clear out the system by

drinking plenty of water. Together with the fasting, this clears and tones up

the body. For anyone living in luxury, how can they take to the spiritual life?

It can’t go together. That’s why many of those coming from the West

get ill — they are spoilt by every sort of comfort. I tell you, the hard

life is absolutely necessary.

I wonder if you could

end by telling us something about the benefits of the spiritual life?

Oh, oh, oh — there is no end to the benefits. On the superficial level,

just look: there are no worldly distractions, you don’t have to go out

visiting people, or doing useless things. Once you give up these things you

can live a private life, a life of seclusion. People used to leave their homes

and live alone, but this is difficult. Ashram life is the next best thing, although

you have to put up with all sorts of temperaments.

I will tell you one last thing. For me coming to India was not really a new life: I was interested in this from the beginning. I never had to give up anything as I was always out of place there.

In the early days Mataji asked me what I wanted.

I said one word: “Enlightenment.”

She replied: “All right. Then sit perfectly still in meditation” .

The passionate story of Atmananda’s fifty-year spiritual quest in India is vividly related in the book, “Death Must Die”, compiled from her diaries which Ram Alexander edited and which was published by Indica Books, Varanasi, in 2000. Her extraordinary death four years after giving the above Interview is poignantly described by Ram Alexander in his epilogue: “Atmananda’s exit from this world was that of a true yogini – sitting upright repeating her Guru’s name with complete composure…she was taken in procession, in the traditional manner for a sannyasi, to a special area of the Ganges reserved for the submersion of sannyasis…Atmananda was given the full honours due to her as a Hindu sannyasi. To my knowledge she is the only Western woman who has ever been accorded such an honour”. |

|

|