43

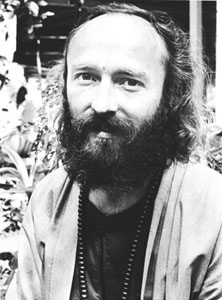

Swami Prem Pramod

Shree

Bhagwan Rajneesh Ashram

Poona

14th February 1981

Leela wants me to meet Pramod, but he is delayed. I am shown round the Ashram which has developed within a matter of 7 years into a designer sprawl now covering many acres. The devotees come from every country in the world, but I can see they are all well over the age of 30. I can also see that they must have or had careers that bring in money: in this Ashram enlightenment (intensive or otherwise) is not free nor according to donations one can afford. For each course or session, even to hear Bhagwan lecture, there are fixed fees!

The whole Rajneesh phenomenon is a daring experiment, and as such has caused much misunderstanding, ridicule, abuse. I begin to see why most of the devotees are laughing: they are freer and happier. Rajneesh is an extension of their psychiatric therapies. Being here is one long therapy. Rajneesh may be helping thousands of Westerners, but not by the traditional Indian teachings, hence so much hostility.

Pramod has arrived. He is wearing a long robe of faded beetroot — my wife’s favorite colour. He is a serious guy who has learned to laugh, and what is especially attractive, he laughs at himself. I can see he could have been in a position of importance in his Western life, but here he is wearing flowing robes like all the men and floating about rather care-free although I suspect he is not allowed to waste his brain.

Interview 43

My legal name is Brian Gibb. I’m Scottish, born near Glasgow in 1948. I studied at Glasgow University — politics, philosophy — and when I left decided to go into politics, and that took the form of joining the Diplomatic Service. I worked in the Foreign Office in London, then I was posted abroad to Brussels to work in the British Delegation to the European Communities. At that time Britain was negotiating entry into the Common Market — a hectic period, ministers were running, treaties were being signed; we worked twenty hours a day. What happened was this: I was married when I lived in Brussels, and after three years I decided I didn’t want to be in politics anymore: I looked at the people twenty years older than me and I could see their lives were dead. They weren’t doing anything that was fulfilling them. I resigned from the Foreign Office — this was in 1974 — moved back to Britain and started getting involved in yoga.

Where was this?

It was in Edinburgh where people who had been involved with Sufis were running

a Centre. I found I enjoyed yoga. I felt I could run, and jump and

float — I was alive. After I had been to one of these sessions I came

out and met some friends, so we went to a pub. When I opened the door I couldn’t

go in: I could smell this atmosphere of smoke and beer and bodies, and I was

so high it felt like I was walking into poison. Anyhow, after doing yoga for two years — I had moved

back to Belgium to teach English — I decided I would like to teach yoga, and that to do that I would have

to come to India to study. So in the summer of 1976 I went to the Yoga Niketan Ashram in Rishikesh: it

was orthodox Hindu and the people there were into studying religious texts,

doing japa, mantras, being devout, living disciplined

lives. It was austere and the food was extremely simple. There was a rigid division

between men and women. I felt the yoga was fine as far as it went, but

nothing was really happening: the place was kind of dead, there was no joy there.

I remember I went out to buy cakes and tea and have a good time, and I got a scolding when I got back because I was not being serious enough. I was sharing a room with a German, and he had a book by Bhagwan Rajneesh, so one rainy monsoon afternoon I picked it up and became intensely interested in it — it was the first time I had come across an Indian guru who seemed to understand the Western mind. He referred to people like Gurdjieff, Castaneda and people I would have thought a guru in India wouldn’t know much about. In a library I found a few more books by Bhagwan, but I didn’t know anything about him. I was still committed to yoga so I went to other places in northern India including Dharamsala, but nowhere could I find what I was looking for.

I was searching for a deeper level than hatha yoga but I couldn’t find a teacher that would inspire me. I became frustrated as I only had a month left before I had to go back to Brussels. I didn’t know what was happening in Poona, yet I felt an urge to come here. And I remember the moment I came through the gates I burst out laughing. I didn’t know why, but I just started laughing. I laughed all the way to the reception office; there was a pretty girl sitting there, and behind her was a board advertising encounter groups, hypnotherapy, Gestalt — it was strange. I had been carrying a book about primal therapy, and I was sure it wasn’t happening outside America yet it was all happening here. And all the people seemed to be Westerners…

And they were all laughing

too?

Yes. I couldn’t understand what was going on — and Bhagwan was speaking

in Hindi during that period, so that didn’t help. Four days later I was

doing an encounter group; I had no idea what would happen. Within half an hour

people were going insane; they were beating their heads against padded walls,

men and women fighting, others were just screaming and screaming. I sat in a

corner petrified wondering what the hell I was doing here. There was another

level of me intensely excited seeing people willing to expose parts of themselves

we usually try to hide. This was a seven-day group and the more it went on the

more people revealed themselves, the more honest they started to be. The parts

they were showing were the parts they always suppressed, like the violence,

the fear, the stunted parts we don’t want anyone to see. It was like an

unfolding of our dark side, and I started to feel this coming up in me as well

— things I had never been aware of.

Can you say what they

were?

Oh, they were memories of childhood, of school, of my first relationships with

women, my parents, things that had been hurtful without my being aware of them

— this started boiling out. But eventually our faces became unrecognisable,

something was being washed away from our faces. Our eyes became brighter, you

could see people’s bodies had a different tone. There were tremendous

oscillations: people could go from violence, cursing, vomiting, and within half

an hour they were tender, loving, they were like little babies. In the centre

of all this there was a therapist called Teertha, an Englishman: I had never

come across anyone like this before — what to say? — I can say he

reads people’s minds. I saw him doing it. He would say to somebody: You’re

thinking such-and-such — the person would stop frozen because it was right.

Then Teertha would add: And that’s bull-shit. I could see he was seeing

things in people that weren’t visible to normal perception, and he created

situations for people all the time. He could be tremendously cruel and say things

that shattered, but still there was a loving side too. I was completely fascinated

by him and at the end of the group I wanted him to be my guru. But I knew this Teertha was a disciple

of Bhagwan, so something else must be possible.

How long did it take

before you heard Bhagwan speak in English?

Two weeks.

What were your impressions?

He spoke on Zen. I went with all kinds of expectations — great revelations,

deep insights, I was expecting to feel the power of his presence, I expected

to learn something — like I knew he knew something. And I was extremely

disappointed: he seemed to be talking about things I already knew reformulated

in a poetic way. Of course, I admired the way he could speak for an hour and

a half with no notes in a language that was not his mother tongue. It didn’t

move anything inside me and I felt disappointed. Yet I could see that others

were very affected by him, they were being transformed unlike anywhere else

— they were glowing, joyful — do these sound like banalities? Well.

I could see something was happening very deeply to other people. I couldn’t

feel it.

But what did you think

was the cause?

It may have been a distrust in gurus: I had friends in the West who

had gurus. But I thought it a weakness for

anyone to need a master — I could see that they could be further along

the Path, but the idea of surrendering to someone and saying: My master, and

to follow whatever he told you to do seemed to me was for those wanting a father

figure or incapable of directing their own lives and needing an external support.

So that was there between him and me, and I didn’t want to have anything

to do with that. I wanted to get something from him but I didn’t want

to give anything to him. And at the same time I knew if I was to accept him

as my master it meant coming to live in India — you have to be with your

master and I didn’t want to be in India: I hated India.

How long ago was all

that taking place?

1976. I struggled. I did a few more groups. One involved something that doesn’t

happen now: it included esoteric meditations, experiencing the astral body,

experiencing death by using the Tibetan Book of the Dead techniques…

Why was that form of

meditation stopped?

I don’t know why, it seemed to be a stage in Bhagwan’s work. In

the early days it was a sort of come-on. Now he calls it a lot of esoteric bull-shit

— auras, the seven bodies, the esoteric significance of this and that,

and this group was like that. It was built on Tibetan and Sufi techniques and

different mystery schools. The whole focus has gone towards more mundane meditations

and therapy groups, but at that time it was intensely exciting for me. I became

deeply connected to the people here. In one way I saw I wasn’t open to

Bhagwan – there was a distrust, a holding back, a resistance or fear,

and yet I felt what was happening here was good. I had to take sannyas

or not take sannyas

as I was supposed to go back to my job in Belgium.

Can you explain what

taking sannyas

from Bhagwan actually means?

I took it before I went back. On the superficial level it means you undertake

to take the new name Bhagwan gives you, to wear orange or red clothes, to wear

the wooden mala which contains his photograph,

you are to practice one of the proscribed meditation techniques every day. Those

are the externals: giving up your name, your blue jeans and wearing a necklace.

But if you go back to

the West must you wear your robes?

Oh, yes. When I went back to tidy up everything for a month I did wear these

clothes and used my new name.

Didn’t people start

touching your feet thinking you a holy man?

That has only happened in India (laughing). I went back and I actually started

a Rajneesh meditation centre in Brussels. I needed to earn some money so I got

a job as a temporary school bus driver.

Wearing your flowing

robes?

I wore orange trousers, orange shirts — robes were a bit too much.

What work were you given

here?

I am now head of the translation department — we translate Bhagwan’s

books into seven different languages. I help with the French translations but

I am running the department. We translate the books that we have contracts for

from foreign publishers. There’s a big interest at the moment: twenty

have been put in German, twelve in Japanese, twenty into Dutch and Italian,

and so on.

How many Sannyasis

are working here on a permanent basis?

I would say about 1,700. There are another few hundred living here who don’t

work in the Ashram. Then there are usually about 3,000 people in Poona staying

in hotels or rooms for about three to six month periods. They come for the groups,

the meditation techniques, the various therapies and also Bhagwan’s morning

lectures.

Can you give a breakdown

of all these different activities?

Every day there are 2 meditations: 1 at 6 a.m. dynamic — extremely physical

in its orientation, and at 5 p.m., Kundalini — another active meditation.

The day is filled with Sufi dancing, tai chi, karate, hatha yoga. The therapies include: primal,

Gestalt — every type that has evolved in the West plus several that are

original to Poona. Then there is: acupuncture, Alexander Technique, Rolfing.

We have people working on themselves, and on the other hand a community living

and working here in a vast number of jobs in the kitchens, gardens, cosmetic

manufacturing, book-binding, craft-work. There’s a children’s school,

a dentist, a shoe-maker — it’s a small town. For them it is a normal

day — a work day. The centre of the day is Bhagwan’s lecture. In

the evening he initiates new sannyasis

and works directly on the energy of other sannyasis

through various ways. Then, as I say, during the day we play at being workers.

What is your relationship

to Bhagwan now after taking sannyas?

I realized after a time why I had this resistance to Bhagwan — I wanted

to be a master myself….(much laughter). I was very sure of myself when

I came here, thinking that I could do anything. There was a lot of pride in

my intellect. As I said earlier: I wanted to get, I didn’t want to give.

For my first year my whole orientation was to learn as much as possible, and

all with the aim of absorbing it as knowledge that would be mine and I could

use with other people. I had had this idea of being a yoga teacher, now I had this new idea

that I was going to be a master, somebody who could teach. I wrote notes every

evening so that I wouldn’t forget anything, and I wanted to be acknowledged

as somebody very special. I wanted him to see how bright I was, how incisive

and penetrating my intellect was, and what a tremendous understanding I had!

And of course none of this was happening — no attention was paid to me.

I could speak to him at darshan, but I never felt somehow he

could see how really wonderful I was.

I had seen how Teertha operated, I had seen how other group leaders operated, and so I became convinced that I would be a truly outstanding therapist. My aim was to be one of the great psychotherapists. So because of all that, nothing was happening between me and Bhagwan — while I was intent on being me, nothing was possible. When I first asked to stay here and work, at the back of my mind was that I should be a therapist here. What I was given was work in the book export office, immediately surrounded by huge account books, invoices, orders — it was totally absurd: I thought I had escaped from all this when I had left the Diplomatic Service. It hurt, it hurt. I couldn’t understand what was going on.

How long did they keep

you doing this work?

I did it for four months and was suffering; every night I came out of the office

drained, pissed-off, frustrated: What the hell are you doing here? I kept writing

to Bhagwan saying: Look, I don’t like this work — I want to be joyful

— why should I do something that makes me suffer? — I’m here

to learn to be ecstatic — aren’t we here to follow our spontaneous

wishes? Each time the reply was: Float joyfully with your work not bringing

the mind into it. Don’t bring my mind to this work? I use my mind seven

hours a day sitting pouring through stupid books. I went on complaining. Eventually

he told me to drop the work. It was a relief, but now there was nothing to do.

After two weeks I went to see Lakshmi, who is Bhagwan’s go-between, and

asked for some work. The message came: If you want to work go back to the office.

Tremendous rebellion, tremendous anger, and I wrote a question which he answered

during the next discourse — it was: Are there any limits to surrender

to a Master when my own inner voice says no to what I am being told to do? Should

I follow the inner voice or the Master?

Enter, stage right, Bhagwan the Destroyer: he answered this question — let me tell you — he said: Do you think for a single second you have ever been surrendered to me? I have been watching you closely. Not for a single second have you ever surrendered — you have only done what you wanted to do. Whenever you were asked to do something that didn’t accord with your wishes, you immediately resisted. I don’t want to make you suffer: you can drop sannyas; there is no need for you to be here suffering… and he went on and on and on, boom-boom, hitting me on the head for about half an hour. There I was wishing the floor would open up and I could disappear.

And when he read out

your question I presume he mentioned you by name?

Exactly. Everybody knew he was talking about me. Afterwards a lot of people

said: I have never heard anybody get such a heavy stick — as we call it

here. You see, I wanted a privileged position, thinking the therapists were

the closest to Bhagwan, and I wanted to be in the inner circle. Want, want,

want, ha? The opposite happened: I was getting my face rubbed into something

I hated doing, and it was a test of how much I wanted to be here. After this

terrifying public lecture I went back to the office offended, but knowing there

was nothing else I could do. Lakshmi said: We have given somebody else your

job, but wait a few days and help out in the screen-painting. I went there,

and of course, I never went back to work in the office again — all I had

to do was say: Yes, here I am, I’m coming back — and it never happened.

But for weeks I was waiting for it to fall on me again. For two years this was

happening and I was yearning for recognition, to become close, and all the time

Bhagwan was the Destroyer. I could see the desires, but couldn’t let go.

Can you give any other

illustrations of how Bhagwan scrubs?

Scrubs? — oh, you mean cleans us up? Oh, yes….there’s an Englishman

here called Sabhuti who used to be the political correspondent of the Guardian

newspaper. We are the same age, we came the same time, we have the same background

in politics, we are both balding — he’s balder than I am —

and during the last few months at darshan Bhagwan has called me by his

name: Come here, Sabhuti. This has many dimentions: he calls me by somebody

else’s name — does he not know me, I have been here five years —

is he just confusing me with Sabhuti? — is he playing with me? —

is he trying to get at my ego by calling me by someone else’s name? He

calls me once, this I can understand, but three times?

So after the third time, which was three weeks ago, I wrote a note: Dear Bhagwan, I can deceive you no longer. I have to confess I have been masquerading as Sabhuti at darshan and I am now Sabhuti. But I am going through an identity crisis and rapidly moving into schizophrenia. Then I put a p.s. saying: But you can call me Rover and I will still answer. The next time I went to darshan I sat in the front row, he looked at me and said: Come here, Pramod — and he paused with a very sly grin, and went on: Or Sabhuti or whoever you are.

He goes in for a great

deal of joking these days?

A great deal. Yesterday in lecture he said: I have decided to play at being

guru and you have decided to play at

disciples, but sometimes we can reverse our roles: I can play disciple and you

can play Master. One of the main ways Bhagwan works is by this kind of self-contradiction.

He will speak for a week and say we have to move into love, into deep relationships,

to experience all the possibilities of the heart: then we all decide we must

find our soul-mate and move deep into tantra or sex. And the next week: No!

Meditation is the only way — if sexual energy is there, just watch, don’t

express it. All the time he is just consistantly contradicting himself: the

only thing that remains consistant are his contradictions.

He gives them out during

his lectures?

Look what he did today. He has said in the past that homosexuality is a perversion

brought about by certain social conditions, and so on. So anyone here who happens

to be homosexual immediately gets a guilt trip. So this morning at lecture a

guy says: Bhagwan, you say homosexuality is a perversion. How can you say that?

I feel so ugly, so unwanted, so rejected. Then Bhagwan suddenly says: Yes, well

I said that last week, but today — well — homosexuality is a new

dimension in human consciousness, no animal is homosexual — we are moving

beyond animals. This is a new possibility; everyone has to go through it —

it is the flowering of human potentials.

At the moment he seems

to be throwing a lot of bombs at public figures.

He’s very rude about them, especially if they happen to be religious leaders

or politicians — he is never nice to them. The only person he sometimes

praises is Krishnamurti. Occasionally he will say that Krishnamurti is enlightened,

but not a master in that he teaches but does not take disciples to himself;

but then he will add that this is because Krishnamurti is still suffering from

his childhood upbringing with Annie Besant and Leadbeater, and that he is not

free from his conditioning when he was being groomed into becoming the Saviour

of the Theosophical Society. So he will say

he is enlightened yet suffering from conditioning, which two things are completely

contradictory. What to make of it? Nothing. He works in situations where people

get trapped in their minds.

Is this one of the reasons

he gets on the whole a bad press?

He consciously sets out to do it. He wishes to make his message known to as

many people as possible, and one of the ways is by being outrageous. He says

for instance that if you are to transcend sex the only way to do it is to go

into it totally, go through it, not to repress it, and in the end it drops away

because you are no longer interested in it.

But in this free-range

Ashram has it ever happened here? Has anyone become celibate through having

too much sex?

A few…yes, I know several people.

Are Bhagwan’s sexual

habits known? What scene is he playing at the moment?

As far as anybody knows Bhagwan is completely celibate — there’s

no doubt about it. In a commune like this, there’s no way a thing like

that could be concealed — we all live on top of each other. You probably

know, Bhagwan never leaves his room, nobody goes into his room except Lakshmi

on business, and Lakshmi is the furthest person removed from sex imaginable.

Is it known why he doesn’t

leave his room?

I suppose it’s because there’s nothing he wants to do anywhere anymore:

his total energy is solely involved with his disciples – on a physical

level at lectures and at darshans. He has said there is nothing

he wants to do, he has seen it as, it’s finished: the only thing left

is his work. In his room he is working in some way.

What is the state of

Bhagwan’s health? And is it because of his health that everyone is carefully

sniffed before being allowed to pass into the hall for his lecture?

He is allergic to strong smells particularly perfumes, and in India especially

Indians tend to wear a lot of strong smelling perfumes and hair oils. That disturbs

him in some way I believe. We are all exhuming smells of some kind, and I know

other people in the Ashram that can detect people’s emotional states by

the way they smell. I imagine he has a higher sensitivity. You can tell when

a person is a vegetarian or non-vegetarian for a start. Fear has a certain smell

to it. Anger also.

In this Ashram the sensual

appetites are not restricted, yet only vegetarian food is served in the restaurant.

Why?

First of all no one is prevented from going outside to get a steak or beer.

That isn’t part

of your sannyas?

No. It happens to be part of the Ashram structure. Bhagwan says he has no moral

objection to meat-eating; it is an aesthetic principle. He doesn’t see

why animals should be killed for us to eat when there is plenty of other food

available. He thinks that ugly, not immoral. He is actually revolted by the

smell of meat-eaters. He told one girl directly he wondered why each time she

came to see him he felt nauseous, then he realized she had been eating meat

and the smell made him sick. I have been a vegetarian for seven years —

you can smell a difference in people.

Is there a strong family

feeling amongst the Ashramites? And what is your relationship to Bhagwan?

I would say very much so. Bhagwan is part of the family. He says he has now

found his people, the people he was looking for. Perhaps that is why there is

now more self-mockery and destroying the image of himself as the guru. We enjoy that joke, but in a sense

what he says is true, yet he is still working on us. We all feel we are doing

our individual work directly for him; for example the gardeners who grow his

vegetables put a lot of devotional evergy into growing vegetables for Bhagwan.

They make his garden round his house extremely beautiful — a lot of love

goes into that. The people producing his books have a feeling that they are

doing it directly for him. Like I’m not working as a translator because

I want to be a translator: the work is his work. We are writing to him and we

get his replies: what form of meditation we should take, what type of work is

best for us.

Do you know of anyone

writing to say they have seen Bhagwan in dreams or visions or meditation?

I have never written anything like that, but I can give you an example I know

about. There was an American sannyasin,

Chinmaya. He is now dead. He had cancer and was slowly deteriorating. He was

in great pain towards the end, and one night he had a strong sensation of Bhagwan

coming to his room; he felt a whiteness approaching him and what he considered

Bhagwan’s finger touching his forehead. He was able to fall asleep immediately

afterwards although he hadn’t been able to sleep for a week. This happened

a second time a few nights later. He wrote to Bhagwan asking if this was his

imagination. His reply was: It was not your imagination. Bhagwan later mentioned

this in a lecture. There have been other instances when people have felt Bhagwan

has come to them, that he was giving them a message.