3

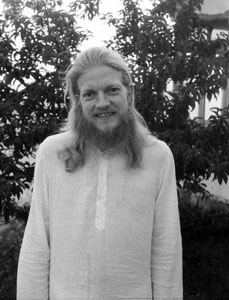

Brahmachari Gadadhar

Sri

Anandamayi Ma Ashram

Kankhal, Hardwar

30th November 1980

Ram wishes to postpone his Interview. In a generous gesture, he gives me his recordings of the late Beethoven quartets as compensation.

However picturesque ancient dharamsalas are, there is something to be said for modern luxuries such as running water, a chair on which to keep your things, or an electric fan to frustrate the flies. Although this is winter and there are no flies, two nights of dharamsala life is enough. I move into the nearby Government Tourist Bungalow where my room has two chairs but the water is off and so is the electricity.

Well, as I said, this is winter so who needs a fan? It’s the best season in India but this place is empty. I enjoy the view of the Ganges and the two chairs. It’s peaceful and private.

Ram has arranged for me to meet a young American who, like himself, is allowed to live inside the Ashram of Anandamayi Ma. I find him cool and casual and speaking in a slow southern drawl — well, it sounds southern to me. He is a brahmachari, a celibate ascetic, so he is wearing white, and what with his long pale hair he looks younger than his age. I am too quick to admire his frankness about Ashram life and as it affects him: he is certainly in the middle of an orthodox Ashram scene not geared to deal with many Western outsiders let alone to encourage them to integrate. From time to time he pauses to polish down what he has said – there must be no repercussions. If you want to live near your guru, it’s best to conform, no need to annoy anyone.

Interview 3

I was born in Oklahoma City. I first came to India in 1969 when I was 21 with the urge to live with Tibetan Lamas. I had read books on Eastern philosophy, on Taoism and Buddhism. One book I liked a lot was Alexandra David Neel’s Secret Oral Teachings in Tibetan Buddhist Sects. Eastern philosophy seemed to fit in with the understanding I was coming up with. I was with Kalu Rinpoche for some time. I was interested in Meher Baba, but he had just left the body so I went to Nepal.

After about two months I returned to the United States where I met an American Swami, and I stayed with him for four years in his monastery. It was very orthodox with orthodox rules, so I learned a lot about Hinduism there. I had good and bad experiences at that place.

Did you have a job at

the time or were you studying?

I was just living there. A lot of money had been given to me, mostly an inheritance,

so I gave nearly all of it to that creep. Then after a while he threw me out.

You must have been extremely

disillusioned. Do you want me to leave all that in? (He obliterates the creep’s

name).

We get helped on the way by all sorts of people.

But wasn’t it a

setback to be made to leave?

I didn’t really fit into the place. I looked on the man as a guru, and at one time I would have died

for him, I was so devoted. But there were many things about the situation that

weren’t correct. These people were devotees of Ma Anandamayi and I had

come again to India with them to see her in 1971. When they threw me out two

years later, Mother took me in and I have lived here almost constantly ever

since.

How does your family

relate to all this?

Being in that monastery in the States was hard on my parents because I wasn’t

allowed to speak to them. Under the influence of that person I treated them

badly — it was the cool thing to criticize so-called worldly people and

to speak about one’s parents as demonic. I should have known better. I

treated them bad until I came to Mother who teaches we should honour our parents.

When a devotee takes sannyas and becomes a renunciate, the monastic life calls for some separation. But there must be a kind of honouring of the parents. Adi Shankaracharya was a great Swami, but he went to his mother when she was leaving the body and he himself performed the cremation. The whole thing of treating parents like dogs when a person enters monastic life is wrong. Slowly over the years the relationship with my parents improved. They have been to India to meet Mother and like her, and they now accept my way of life. They are much more in agreement now. They would like me to stay with them and get married and have kids and all that, but they are now to a certain extent resigned to what I’m doing.

Can you give a description

of your way of life?

For some time now it’s been erratic. I’m supposed to meditate seven

hours a day at least — this is what Mother has recommended for me. I haven’t

been doing that for some time as I have been travelling around getting into

various projects.

What sort of projects?

For a couple of years I was into —

and I still am but not so intensely — collecting tape recordings and photographs

of Mother. I have some good equipment so I have copied close to 200 hours of

Mother talking and singing, and also many rare photos.

Isn’t this regarded

as seva

— selfless service?

In most people’s book it is, but in Mother’s it isn’t. The

last time I visited the States I helped start a center for the distribution

of her photos and tapes. When I came back to India I started distributing them:

the idea was to benefit everyone and also to preserve what I considered to be

treasures. I looked on this work as noble and part of my sadhana.

Whatever I do I do to perfection; it is like worship. In doing something publicly

though I had to deal with the Ashram authorities, and there was some criticism,

both just and unjust. This started disturbing my mind. I spoke to Mother; she

said I should resign from these activities, at least publicly, not to get involved

on an official level. I followed her advice and things are better now. I had

been in charge of the publication of her photos and the tapes for the Ashram,

you see.

Some years ago I asked Mother what seva I could do for her; she said meditation, japa and dhyan, studying scriptures and attending satsang. So this is what she considers real seva — the work that perfects your own nature. One is encouraged to do intensive meditation — maybe not to sit formally, but to concentrate the mind on God. I am now trying to get back into my meditation. I had gotten into travelling a lot so it’s impossible to sit for seven hours.

Have you received a form

of initiation from Mother?

Let’s say I’ve had initiation in Mother’s presence. She says

God gives the initiation, and that God is the guru. We view initiation and the guru from a condition of ignorance: we

have the notion we “got” something we didn’t have before from

a guru. To Mother there’s only one

— all creation is her own. One can experience a multitude of relationships

with her as well, but she doesn’t admit to any definition as definitive.

She doesn’t deny our ideas we have about her either — she simply

urges us to a fuller understanding.

Is there a formal initiation?

There can be a formal initiation… it can take various forms… but

there is definitely an initiation. For some it can be formal: they take fruits

and flowers, sweets and cloth, various items for the ceremony. The procedure

isn’t supposed to be talked about. Everyone who comes to Mother, their

sadhana

and meditation is different; they are guided personally by her.

The guidance is given

during private Interviews?

In various ways. Just as initiation can be informal or formal, similarly instruction

can take many forms; during a private Interview, during one’s meditation.

You have adopted a new

name, but does that mean you have renounced the one you were born with?

No, occasionally I use it. I was given the name Gadadhar when I was living in

that monastery. Mother likes it so it hasn’t been changed. Receiving a

spiritual name often accompanies one’s entry into a more committed spiritual

life.

Do you have to become

a renunciate to receive a new name?

No. Many of Mother’s householder devotees take spiritual names. People

like to have a name that’s given by her.

What does yours mean?

Gada is the mace or club held by Narayan. He has four arms; in one hand he holds

sudarshan chakra, in another a lotus, in another

there’s a conch, and in the fourth the mace. So Gada is the mace, and

dhar means the holder of — the holder of the mace. Gadadhar was also the

name of Ramakrishna Paramahansa when he was a boy.

Many of Mother’s

followers wear orange — you are wearing white. Can you tell me if there’s

a difference?

Orange denotes a high level of renunciation, a firm monastic commitment for

life. Anyone wearing white can eventually marry. In traditional Hindu life everyone

should be brahmachari — that is chaste, and

wear white up to the age of about 25. Then they have the choice of either marrying

or becoming a renunciate for life, which is rare. Most people are not cut out

for that austere way so they are encouraged to marry. I am trying to lead a

brahmachari life, but the intensity of

my renunciation has evidently not become enough for Mother to consider it appropriate

for me to wear orange.

Is that your aim?

I don’t know. I want to surrender to Mother’s will — if she

wanted me to marry, I would go that way; should she later want me to take the

orange robe, that’s fine too.

But as you are still

so young, do you not find living a celibate life difficult?

I practice it because it’s pleasing to Mother. There are scientific reasons

extolling brahmacharya such as conserving energy which is then channeled into

one’s meditation, and that energy can take you into higher consciousness.

There are health reasons, and it helps one’s concentration also. Too much

involvement with worldly people — emotionally as well as physically —

can disturb the mind. Until a person is established in his meditation he should

observe moderation, aloofness with the world. This means not only sexually but

in all his dealings so that his attention is directed inside. These are some

of the main reasons given in favour of brahmacharya; for me the main reason

is because I think it is pleasing to God. It is not necessary for everyone to

take to that way, though — many people around Mother are married, and

their lives are pleasing to her.

But has it ever been

a problem for you?

At certain times, but only on a childish level, which to most people would be

nothing. It hasn’t been serious as there’s no desire behind it.

It’s not something I can’t control. It’s just annoying if

things come up — I’m just a person. Sexuality is one of the last

things to go; even the rishis

and sages until they’ve attained enlightenment still have traces of sexuality

which come up occasionally. So although that thing is there, it’s not

so serious that I can’t practice brahmacharya. If a person finds brahmacharya

really difficult it should be given up; the urge should be sublimated —

divinised — perhaps by getting married or having some sexual experience

in the right context and frame of mind. Then he can pull himself out of that

condition or desire, and if he can love the person not only for her body or

the physical satisfaction it offered, the whole scene will be raised onto a

high level.

No one should force himself into brahmacharya. I have not done this. I rarely think about it. A person’s evolution takes place over many lives. A controlled life is one of the things pleasing to God.

As a Westerner brought

up in a Western culture, you are now living in an orthodox Hindu Ashram although

you are not a Hindu — you are non-caste. Did you find it difficult to adapt

to this way of life?

I find much in Hindu philosophy and teachings according to my own nature —

even the ideals within Hindu society. I could be called a Hindu, although I

am not accepted as such by orthodox Hindus. I hold to my relationship to Mother

so it doesn’t bother me what others say — I am not this or that.

I am here only to be with Mother and practice sadhana.

It is difficult sometimes. My life in this Ashram by Western standards may not

be all that great. By Indian standards it’s quite nice. This small house

inside the Ashram has everything I need, and it’s kind of the Indians

to allow me to live here.

But one should understand that one need not live in

abject poverty to meditate. I don’t live like the average Hindu. Anyway,

I don’t belong to any one particular culture; my life is in fact a combination

of both Western and Hindu cultures. And I feel at home in both place.

|

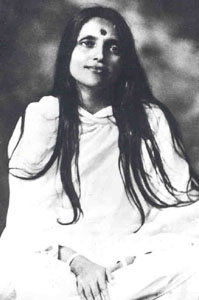

| Sri Anandamayi Ma |

| Gadadhar died the ideal devotees’s death one year after this Interview. He was in his early thirties. Vijayananda, (Interview No. 1) seeing Gadadhar had slipped into a hepatitis coma, rushed him to Delhi hoping that a blood transfusion would save him. He died before this could be arranged. At that time Anandamayi Ma was attending the Kumbha Mela at Allahabad where millions of pilgrims gather for this festival. She was extremely ill but remarked she had clearly seen, as did others in her entourage, Gadadhar on the day of his death ecstatically dancing in the big bathing procession. |