22

Dhruva

Cottage Guest House

Sri

Aurobindo Ashram

Pondicherry

23rd January 1981

Sri Aurobindo was a philosopher, poet and mystic who had been imprisoned by the British Raj for sedition. In 1910 he took asylum in French Pondicherry which he never left for the remainder of his 40 years. Here he wrote many profoundly influential books. He drew devotees from all over India and latterly from abroad including the French born Mira Richard who became his alter ego, his spiritual muse, his link with the outside world, the builder of his Ashram. She was known simply as Mother. Sri Aurobindo died in 1950. The spiritual work was carried on by the powerful but loving Mother until 1974 when she too left this physical world. Since then there has been no official spiritual or physical head to run the Ashram.

It is just as well I have arrived early: the manager of the Cottage Guest House — part of the Sri Aurobindo Ashram — tells me no letter requesting accommodation ever arrived. After an uncomfortable few minutes of friendly questioning, he gives me a room. And it’s cool, well-designed, clean and reasonable. This, I notice, is one of the Ashram’s essential characteristics.

Whatever they do, whatever they make is done and made

to perfection.

I am given tickets which will allow me to eat in the communal dining hall. Pondicherry

has a North African resort atmosphere with its palm trees, permanent blue sky,

its street signs in French. I can’t help thinking the heat in summer must

be unbearable.

The Ashram buildings are spread out over a section of the town — they are part of the town — and are unlike any other Ashram I know. These buildings were former private houses of much character dating from French colonial times.

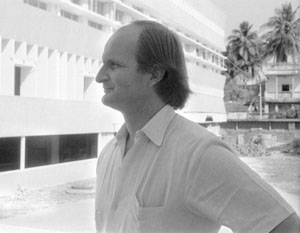

During my stay, there is much publicity concerning the Indian Government threatening to take over Auroville,(1) but I will avoid all this; it’s of no relevance to these Interviews. On the notice board in the main Ashram I see there’s to be a general meditation session in the sports ground. That pleases me; at the end perhaps I will meet someone who can suggest Interviewable subjects. Dhruva is the perfect person: he assures me there’s no shortage. He is American — so many Americans I’m meeting! — and as he walks me back to the guest house he says by the morning he will have a short-list ready. I tell him something of my Ashram-hopping adventures: he is so thrilled by the one-day-too-soon Agra story he makes me repeat it and declares it nothing less than a miracle.

It is now arranged that he himself will give the first Interview very early in the morning in my room before breakfast (he must then attend his work at the hospital). This means we will begin the day with something more nourishing than food.

Interview 22

Can you start by telling me the meaning of your

name and how you were drawn into this new life?

Dhruva is the name the Mother gave me in 1970: she gave the words, Firm, Fixed,

Resolute — they were translated into Dhruva. It’s also the name

of the Pole Star, the symbol of constancy. Mother usually named people in terms

of the qualities needing to be developed, you see.

Well, I was born in Massachusetts but was brought up in California. Under quiet protest I went to school and managed to get a B.A. in anthropology more or less by accident. For a while I had a literary theatre in San Francisco and lost a pile of money. When that was closing down I met a fellow involved in the esoteric: mainly Egyptian geometry and mathematics. He was on his way to India to find his guru; but about the time he arrived in Pondicherry, without me knowing what he was doing, I found a book of Sri Aurobindo. Later when I arrived here, that connection developed.

I first wrote to the Mother in 1966, and that was the beginning of the confirmation from her that there was an inner receptivity which might be developed. I came, and here you find me — the therapeutic work I’m doing began here.

Can you describe this work?

It’s mainly the alternate modalities of acupuncture and osteopathy, and

some homeopathy. I work at one of the Ashram clinics. There’s one main

dispensary and also a surgical clinic and nursing home which I work in.

Is this run on a voluntary

basis or do people have to pay for treatment?

A mixture. At the main dispensary anyone living as a member of the Ashram or

Auroville can get free treatment. If they want to put something in the box,

that’s all right. It’s supported by Ashram funds. In the clinic

where I’m working, anyone can come for treatment and pay normal fees,

though Ashram residents are treated free, of course.

What was it like meeting

the Mother?

I met her on the day of my arrival — eighth February 1968. I had never

been out of the United States before. The plane was late, India was overwhelming,

and the scheduled meeting was two or three hours late also. The room was full

of people, and at that time there was no great revelatory experience, partly

because it was early in my inner development, and partly because of the sensory

overload of just being in India. There were later experiences, but the most

dramatic in its impact was -- I think it was New Year’s Day 1971.

Mother had been extremely ill and hadn’t been seeing anyone…she was over 90 then! At Christmas she had had biscuits distributed with a card saying: Persevere. But on New Year’s Day she allowed the heads of the departments to see her; afterwards she said: Maybe I’ll see a few more people. She ended up seeing 600! I was at the tail-end of the procession, so when someone called me, I literally ran up the stairs. I was unprepared and therefore more open…that was a very powerful time.

Had Mother been associated

with Sri

Aurobindo from the beginning of his mission?

He came to Pondicherry in 1910 after a period in jail in Calcutta for his political

activities. In jail he had certain inner experiences which gave him the opening

to the possibility of this yoga, and from then he was engaged in

intense sadhana.

The Mother, who was French, came here in 1914 with her then husband, Paul Richard.

She later said that she had never surrendered to any entity other than the idea

of the Divine. When she met Sri

Aurobindo she immediately without question gave everything. She made the extraordinary

statement that if that was a mistake it was the mistake of the whole being.

When the First World War came she went back to France. She later spent several years in Japan but returned to Sri Aurobindo and Pondicherry in 1920. Until her death 53 years later she never left. In 1926 Sri Aurobindo had an experience which was described as Krishna coming into the cells of his body; after this — for 24 years, that’s until his passing — he never went outside his room. From that day in 1926 the Ashram came into existence; through the Mother, the building up of the Ashram and the selecting of those destined to live and work in it took place.

What is the nature of

the yoga and sadhana

which has evolved?

One of the difficulties about talking about it is that it can only come through

one’s own understanding, which is limited…and one is in danger of

speaking in platitudes and jargon. Well, let’s try. Sri

Aurobindo came to spirituality through an intense love for India; he wanted

power to free India, so he took to yoga. Then all these other things started

happening.

Basically he says that each of the traditional yogas take up one aspect of the human

experience: hatha yoga deals with the purification

and suppleness of the body to make it an instrument to receive; in bhakti yoga the heart is opened; in

jnana yoga, the mind; in tantric yoga, the experiences of occult power

and unity…and so on. Each of these paths is a kind of linear opening through

a particular faculty in the human make-up, the theory being that as the Divine

is everywhere it doesn’t matter where you touch it as long as you touch

it. Once that is done the work is done.

But Sri Aurobindo felt that wasn’t sufficient as each yoga — and each religion — represents in its essence a surrender of that part to the Divine whereas essentially the totality of the human experience has to be surrendered. It became clear to him that the symbol — you can call it the reality — through which that surrender is made is the Divine Shakti, the Divine Mother. He became so identified with that quality of Divinity that for some time he signed his name Kali. He felt the surrender of the total being was the preparation of the body for a greater role to play in the higher scheme. This surrender could bring into the earth’s atmosphere a consciousness which up till now has been attainable only by leaving the earth plane in samadhi.

This plane of consciousness he refers to as the Supermind. But there’s also the Overmind, which as I understand it is the plane of the gods. This is limited by what we might call the seed though not the actual outgrowth of ignorance, because the gods — the power of knowledge, the power of action, the power of love, and so on — function as separate entities. In the Supermind you have all the multiplicity — the action of diversity — which never loses touch with the One, the Divine. His idea was that if that Supramental force — he referred to it as the Truth-consciousness — could come into the earth’s atmosphere and be active instead of implicit, there could be a major evolutionary change in the human make-up. That is what he was working on from 1926.

What was his method of

sadhana

to achieve this?

He said surrender to the Mother was the only effective method…

Do you mean the Mother

Kali or the living Mother?

…the Mother who came here, the French lady — she was the embodiment

of the Divine Mother. So for those doing his sadhana,

the surrender to her symbolically and in physical fact is the ultimate symbol

which enables a far deeper thing to happen than just doing what she may say

at a particular moment. Somebody asked Sri

Aurobindo in the early thirties: Did your 1926 experience enable you to realize

that Mother was the divine Mother? He said he knew much earlier. Many times

he was told: It’s all well and good for you to do this great sadhana,

but you are you and we are just people. But he would answer: Look, if my being

here has any meaning, it’s only in that it enables others to do what I’ve

done.

So the central technique

of his yoga is surrender?

Surrender, devotion and love for the Mother is the motivation, and through that,

one contacts the Lord. Sri

Aurobindo speaks of the Psychic Being — which is almost the same thing

as the soul: it’s the evolving entity behind the different parts of us,

and it’s that which reincarnates.

For me, Sri

Aurobindo’s experience — his perception — of the third entity,

the Psychic Being, the true individuality that doesn’t lose its touch

with the Divinity, is all important. In Jungian psychology there’s the

constant battle of the ego and the self, the ego having to defend itself all

the time because it knows all the cards are ultimately in the self’s hand,

and the self gradually imposing itself on the ego structure so that the sense

of individuality is in jeopardy at each step. In opening the Psychic Centre,

which Sri

Aurobindo says is behind the heart, that problem doesn’t exist, as this

Centre is the link to our true individuality; its essential qualities are quietness,

delicacy, joy in giving, and a gentle assertiveness. The awakening of the Psychic

Being obviates the dualistic struggle. Sri

Aurobindo’s suggestion is also that we don’t have to dump the body

— of evolutionary necessity we shouldn’t do it.

For this yoga is there a form of initiation and

ethical rules or a special meditation technique?

The general answer to all that is No. In my case, perhaps an initiation took

place when I first wrote to Mother saying I had a problem of being lonely…to

which she replied: Those lonely in the world are ready for union with the Divine.

This was the confirmation that something could happen. The Ashram is basically

vegetarian, but there’s no rule about that; it’s just felt there

are better ways to be nourished than by eating meat. The Mother didn’t

want a lot of rules because of the variety of ways people get to where they

are going.

There are however 4 Ashram Rules: No sex, no politics, no smoking, no drinking. When the drug thing happened that was included in the no smoking and drinking. The no politics rule was once explained by Mother in a tape-recorded talk: After Sri Aurobindo came here, he never again engaged in politics, not because he wasn’t interested in what was going on in the world, but because in order to be a successful politician you have to develop hypocrisy, deceit and so on, which goes against the grain of spiritual development.

Now the sexual question — which is an extremely important one, for the body as it has evolved is made to produce more bodies — is a fairly substantial limitation on many people’s behaviour. In this restriction, Sri Aurobindo said he didn’t mean only the physical act but the vital exchange that can occur between a man and a woman without physical contact. It’s a technical problem in the sadhana, not a moral one. One is trying to do something else with the energy; the sexual energy is the energy of change which if used in the ordinary way drains away the chance of the ultimate change — the settling in of the higher consciousness. This cannot be attained if the energy flows outwards, sexually.

How does this affect

married couples here?

Sometimes disastrously, sometimes it changes the relationship to a higher, better

level, usually something in between. Sri

Aurobindo himself said it is one of the most difficult areas in the sadhana.

Another writer said: Traditionally by rejecting sexuality, the yogi rejected a whole aspect of physical

existence, but this was valid if that rejection ensured a higher body consciousness,

for the energy continues to have a role…it functions in the sadhana.

You have given such a

vivid outline of the teachings, could you now describe how if affects your daily

life?

I can do that in a general way; personal details may be interesting but not

the crux of the matter. I should say that it wasn’t until I came here

that I had any real life, any focus. I knew there was something I was supposed

to be doing but I certainly wasn’t finding it where I was. The only real

sustenance which kept me together was music, mainly Bach, from the time I was

16. You were a musician so you will understand all that. Mother says somewhere

that it takes a large proportion of one’s sadhana

to simply cancel out the early influences, the lack of clarity, the sub-conscious

habits, all of which are far more powerful than we like to admit. So to get

one’s past into some kind of creative perspective is a major part of our

work.

I didn’t know what I would do here in terms of work, but as soon as the possibility of going into healing work came up, that developed naturally; so that problem was solved. There’s a fundamental change, and when that happened one realized that everything else was a preparation. I was once describing my one drop of understanding of these issues; I said: Is it so difficult to understand that everything is the Divine? And as I said that, I experienced a tremendous…blop! And it was so strong, I was completely out of contact: I had to say to myself I’m not ready for this…if I do this now they will take me off to the looney bin!

When you say not ready,

what do you mean?

The experience of the Divine being in everything, in every tiny bit of existence.

Those experiences come and go, but it take years to develop some stable capacity

to bear a consciousness which is — how to say? — well, which is

not natural to the human frame… let’s put it that way. When people

asked the Mother: How do we know when that thing’s happened? — she

would answer: You know! — if you have to ask the question, it hasn’t

happened.

The only preparation is the aspiration to change, to surrender. We try to change the very fibre of what makes us normally human, which happens to be a great deal more normally animal than we like to admit. If there weren’t that fundamental idea of giving every single moment as an offering, the thing would be impossible — there wouldn’t be a focus.

I saw on the notice board

that tonight there would be a recorded performance of Mozart’s Requiem.

Do you still listen to music?

Oh yes. The Ashram provides a wide variety of possibilities of expression. You

can paint or dance or play basketball. There’s Western and Indian recorded

music. There’s meditation. But no one says: This is what you have to do!

There’s no fixed

daily programme?

No. You probably know there’s also quite a lot of small-size businesses

associated with the Ashram, mostly handicrafts. Early on, Sri

Aurobindo and Mother had to decide whether they were going to do this sadhana

for themselves as a point of leverage for the rest of humanity, or to include

people in the process. They decided to include people; so symbolically they

had to have the whole of humanity here, at all stages of spiritual awareness

from zero to those “highly” evolved. That’s why there are

outlets for everyone. There are in fact about 2,000 people living here permanently

— Indian and non-Indian.

Is there a reason why

Mother didn’t appoint a spiritual successor to carry on the spiritual

work?

When Sri

Aurobindo left, she was there, so it was assumed she would continue his work.

Now there is a problem because a number of people here implicitly or explicitly

have set themselves up as gurus. But this yoga hasn’t been finished yet;

so you can’t be a guru unless the sadhana

has been finished — even Sri

Aurobindo and Mother never finished the process. They just said: If you want

to come along with us, this is what you have to do, this is what’s been

done so far. Sri

Krishna never left a successor. Here

it’s not thought that the Mother has left with her physical passing: her

consciousness is experienceable with a little bit of openness. It’s very

real.

In July 2006 Dhruva gave, as he explained, a

brief summary of his life since our meeting: I was at that time working on a book about the relevance of Indian mythology to the modern world, but it wasn't coming together as I had hoped. So I began exploring Judaism as what I perceived then as the source of the Western spiritual tradition. I realized after some time that something else was happening besides an academic exploration. The final upshot was that in February of 1998 my wife and I had an orthodox Jewish conversion, a path we have been following ever since. My name now is Eytan Grinnell. We moved two years ago from San Diego to Milwaukee to be a part of the Twerski community here. We feel very deeply that this has been the right way for us.” |