18

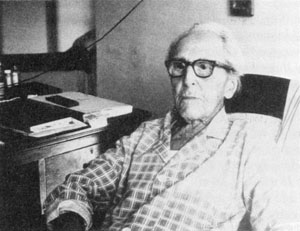

Russell Balfour-Clarke

The Theosophical Society

Adyar

Madras

20th January 1981

Back in the peace and quiet of my solitary dormitory I am writing to Father Bede Griffiths; I would like to fit in a visit to his Ashram after my stay in Pondicherry. But first I have to send a telegramme to the Theosophical Society in Madras, my next port of call. In India when we have a lot of time it’s amusing to pay a visit to village post offices — Westerners are often invited in for chai – Indian spiced sweet tea -- while the clerk unlocks his cupboards looking for air-letters, telegramme forms, rubber stamps and special forms.

I’m supposed to leave for Madras tomorrow but have discovered that the train journey will take 36 hours which means I may be too late for the marriage of Ram and Parvati — my American friends from Anandamayi Ma’s Ashram. They are arranging the ceremony to coincide with my arrival at the Theosophical Society at Adyar (according to a letter from my wife who is now snowed-up in Mussoorie). I was hoping to take their joint Interview on their wedding night.

But here I am at Sarnath’s village post office, tealess, and being told: It is inconvenient to send any telegramme today, could you not go to the main post office in Benares?

Inconvenient? — I ask, trying not to appear too eccentric.

Very — you see, the line, she’s out of order!

I dash all the way into Benares — what else can one do? First I am begging them at the Indian Airlines office for a seat on the afternoon plane, any plane, to Madras. No chance: twenty-nine people on stand-by. So now off to the recommended, hopefully fully functuating, main post office.

In India there is no queuing system: we are all expected to push. The pushing is greater in city post offices…more people, more pushing, the only way to get hold of a telegramme form, hand it back, pass the money, the only way to secure the receipt. The vital sorry-I-will-be-late telegramme finally on its way, I extricate myself, and move away all of a heap.

In the morning I am sitting on the train to Madras dazed at the prospect of a 36 hour journey. The business man opposite me in the compartment laughs: The train — he says — was twelve hours late last week. I am now resigned to missing the wedding, I only hope there will be time for the Interview… Ram and Parvati both have far-out stories.

The train this week is only three hours late, and it’s now night-fall, and I don’t even know if they have a room for me at the Theosophical Society. The businessman lives at Adyar, so we share a taxi and he gets me through the locked iron gate into the T.S. estate. One can’t get in after dark unless known to the gate-keeper.

I find Norma Sastry, the estate secretary and to whom I have been writing unsuccessfully to reserve a room: no reply ever reached me. She looks as if she’s been to a party — Oh, a wedding! — and she gives all the news. Ram and Parvati were lovely, the marriage was lovely, and they have both left this evening for the Ashram of — oh — I just can’t remember, but you do have a room: in Leadbeater Chambers…number 15…Ram has just vacated it.

In the room I find the remnants of a vegetarian party, and on the table, placed so I can’t miss it, a pink telegramme:

PILL ARRIVE ONE DAX LATE FULL LOVE MALCOLM

This is indeed high style post office creative interpretive writing; I had written:

DUE TO TRAVEL AGENT’S BUNGLING WILL ARRIVE ONE DAY LATE. ALL PLANES TO MADRAS FULL. LOVE-MALCOLM

Madras has three seasons: hot, hotter, hottest… this is January only the hot season, but in the morning as I start making arrangements for the first Interview, the southern heat is forcing me to walk in the shade of the ancient trees that line the paths of this exotically landscaped estate, a huge tropical park borderd by ocean and river beaches.

Adyar has been the International Headquarters of the

Theosophical Society for about a century,

and there is one old resident here who remembers its early days of glory –

not quite early enough to have met Madame Blavatsky the co-founder, one of history’s

most enigmatic women who played a major part in opening modern Western minds

to Eastern thought, and who can be regarded as the grandmother of the New Age.

Russell Balfour-Clarke arrived as a very young man over seventy years ago, he

is a walking-talking-history-book. He still rides a bicycle, he still speaks

in ringing English tones, but he isn’t sentimental about the great early

days. His mind sparkles in its clarity and consciousness of expression. I automatically

feel a terrible pang of regret -- how I wish this Interview could be filmed:

one can’t meet a walking-talking-history-book every day, one that spans

almost a whole century.

Interview 18

Before you speak about your early life, may I

ask you if it’s true that you are 96 years old?

No! That’s not correct — I’m only 95.(1)

Hmm…my early life? Well, I am British, born in London in 1885, June 2nd.

My parents were landed gentry — squires — owners of land and farms.

My mother was a Low Church Protestant; my father, because of his love of music,

would often visit Catholic cathedrals to listen to the music although he was

not a Catholic — he was broad minded. I wanted to become an engineer,

and I was accepted at London University for a B.Sc. in engineering, but after

one year I had a six months’ illness with typhoid fever and another six

months to learn to walk again and recover.

One little door-mouse nurse came to look after me; she had a magnetic power, and when I was raving with fever she would put up her hand and say: “Now Dick, be quiet!” — and I was like a lamb.

When I began to think and recover — and this is the way I came to Theosophy — I said to little nurse:

Is there nothing more to be known about God and man than what we learn from the parson?

She gave a strange answer: There is infinitely more to be known.

I said: Where is it? It’s not taught in the Bible.

She replied: It’s mentioned in the Bible — Jesus said, ‘Unto the multitudes I speak in parables, but unto my own I speak of the mysteries of the Kingdom of Heaven’ — that is the further knowledge.

Then she told me about the Theosophical Society in London where I could meet people who had found that wisdom. When I had recovered, I found the Society and went there.

How old were you then?

About 19 or 20 — it was in 1904. There I met Mr. Bertram Keightley who

helped Madame Blavatsky publish her book, Isis Unveiled — her first remarkable

book which made the world sit up prior to founding the T.S. He handed me a form

to fill in; there I read the Society’s three aims:

1) To form a nucleus of the Universal

Brotherhood of Humanity without distinction of race, creed, sex, caste or colour.

2) To encourage the study of Comparative Religion, Philosophy and Science.

3) To investigate unexplained laws of Nature and the powers latent in man.

I was in sympathy with these aims and paid the fee. Later I was sent for and met Col. Olcott, the co-founder of T.S., who handed me my diploma of membership, shook my hand and wished me well. He had a powerful magnetic personality. I then made friends with a staunch Theosophist, Mr. A.P. Sinnett who claimed to have had contact with the Master Kuthumi — he has written about it in a book called, The Occult World. Due to his influence, I wanted to become a Buddhist monk and give up Christianity, but he advised me to follow my career for a while. I was still studying T.S. books but took an apprenticeship on the railways in London which led to an appointment as assistant engineer of construction in Nairobi for two years. That was a world of candles and kerosene oil.

Did you have any contact

there with Theosophists?

No, but I formed a group of three people called the Occult Group. Now I hear

that there is a live T.S. movement in Nairobi. At night in my tent I used to

read Theosophy. I became more and more interested, and when I returned to England

in 1908 I attended lectures by Dr. Annie Besant, the new President of the Society.

I had written to Col. Olcott about becoming a monk, but he had died, and Dr.

Besant replied:

I strongly advise you not to plunge into orthodox Buddhism, but perhaps if we can meet we can discuss it.

After meeting her three times, she said:

I would like a young man like you to see India — today I have been given two thousand pounds to do what I like with, so I invite you as my guest at the International Headquarters of the T.S. at Adyar.

I jumped with joy, but she said: No, no! — think about it for a week, then let me know.

At that time I was also offered a very good job in West Africa; it meant a high salary and a step up in my career. I was at a crossroads. Now, Mr. D.N. Dunlop was a famous Theosophist who had a miniature of two adepts, whom I recognized as the Masters Morya and Kuthumi; he had copies made for me….

They were paintings?

They were photographs of paintings made in Madame Blavatsky’s London studio

I believe; somehow she placed her hand on the painter’s head, he saw the

Masters and painted them. I was thrilled to have these copies, and as I was

at this crossroads, I placed them before me and sent out a plea: If I am worth

being taken notice of by the Society founded at your instigation by H.P.B. (Madame

Blavatsky), could you give me a hint which way to go? I received a definite

sentence in my head: Choose the way of unworldly wisdom, and there will be no

regrets. It was clear.

I arrived here in 1909 with a letter of introduction from Dr. Besant. I was put in room no.7 at Blavatsky Gardens — a very simple room. C.W. Leadbeater had already awakened the kundalini and was cultivating clairvoyance; I went to his Octagonal Bungalow, and told the man leading me to say Dr. Besant had sent me. He went in and said: Dr. Besant has come. I could hear Leadbeater saying inside: Hmm! She must have materialized, let’s go and see. We laughed when we met.

And then I met a shy, sorrowful-looking boy — J. Krishnamurti. He was about 13 years old then. I was 10 years older. Mr. Leadbeater took me into his confidence when he got to know me better and said: Master Kuthumi has asked me and Annie to look after these two children of his, -- at that time Krishnaji’s younger brother was still alive. I was entrusted with the task of helping. What we had to do was to clean up these two boys: they were unhappy, dirty, ill-fed because their mother had died and a very hard-hearted aunt was in charge of the house — the father was not much good with children so they were neglected.

We set to work. It was a great joy to me having come into all this. People point to me now and say: He was Krishnamurti’s teacher. That is not quite true. I was Krishnamurti’s constant companion, his nurse, his valet de chambre. We went cycling and swimming together — yes, and I did teach him his first English. I moved with him closely day and night until his 19th birthday. That was from the beginning of his career until 1915 when I had to go to war and join the army.

There has been some criticism

that the booklet, “At the Feet of the Master” was never written

by Krishnamurti himself during this period. Do you know anything about this?

I certainly do. When Mr. Leadbeater first saw the 13 year old Krishnaji, he was struck by his aura, which

he described as the most wonderful he had ever seen. It could not have been

Krishnaji’s outer appearance that was

striking, for at that time he was undernourished and uncared for. But Leadbeater

took him and his younger brother under his care. The father — who was

a Theosophist — and the other children were given a place to live within

the Society’s grounds. Leadbeater told me Krishnaji was destined to become the World Teacher:

He will undergo spiritual training; there will be opposition but it has to be

done.

Now Mr. Leadbeater had Krishnaji come to him at 5 o’clock every morning and asked him to recollect what the Master KH had taught him on the astral plane during the night while he was out of the body. I was always present so I saw Krishnaji write down the teachings in the form of notes. The only outside help he received was in his spelling and punctuation — you see, he was still learning English. But these were the notes that were later turned into the book, At the Feet of the Master, and published under the name of Alcyone; it has been translated into about thirty languages and gone into forty editions or more. Yes, I know there have been many skeptics who have tried to prove that a boy of 13 could not write such a book. But I saw him with my own eyes; that is my personal testimony.

That is invaluable testimony,

thank you. What happened after you came out of the army?

I became a civilian again in 1924, and Annie Besant suggested I should join

Leadbeater in Australia. I was with him for five years living a strange and

wonderful life. I was initiated into Co-Masonry and into other ceremonial groups

and helped Leadbeater; I cooked his food and nursed him when he was sick. I

toured with him, he made me a priest of the Liberal Catholic Church and I attended

the meetings of the esoteric school of Theosophy and the general meetings. A

very full life. I plunged into all this with enthusiasm and believed that all

I was doing and hearing about were facts.

When you say you believed

in everything then, does it mean that later you had doubts?

Well, I’ll tell you. I don’t doubt, but through the years because

of my strong link with Krishnaji I seemed to be going through, in a

lighter vein of course, what he went through. So now I have to say that in my

book, The Boyhood of J. Krishnamurti, I wrote about things as though I knew

them, but I had been told them by Leadbeater and others and accepted them as

facts. Now I would say that whether they are facts or not I don’t know,

but because I don’t know I can’t deny or affirm.

I see. How did you part

from Mr. Leadbeater?

I married. I came back to London, took a job, but after a time my wife and I

came back here to Adyar where we lived and I was given permission to take a

job in a big engineering firm outside.

Was all this before Krishnamurti

renounced his role as the World Teacher?

Long before, oh, yes, yes…

You were still in contact

with him in those days?

Yes, of course. I met him often. I met him in Australia and observed the painful

fact that Leadbeater, from being affectionately disposed towards him, turned

against him and said everything had gone wrong. Krishnaji later told me how he was asked to

get out of Adyar and never come back. Well — as everyone knows —

he did get out, and it was only a few days ago that after fifty years he was

invited back by the President of the T.S., Mrs. Radha Burnier, and he walked

through these grounds again. I had the pleasure of welcoming him, although I

have been seeing him practically every year when he comes to India. He is now

looking in better health than ever. He is 85, you know — 10 years younger

than me.

All these many years

you have lived in India must have been very fulfilling for you.

Yes, they have. I can say that when I first came to Theosophy, my mind, through

contact with the early Theosophists, was filled with visions of the Wise Men

of the East, the Great Adept Brotherhood, the Hierarchy standing behind the

people who were said to be running the inner government of the world. But all

that has rather faded — I don’t say it isn’t true. Leadbeater

wrote a wonderful book about this, The Masters and the Path. I have been presented

with much teaching and have read many books, but I took into my heart what I

liked and made it my own. But in the past I made a mistake in an effort to help

others by writing and talking about the Masters and what they did and didn’t

do as if I knew. No, whatever progress I have made, I have progressed to this

point of view that much of my belief has fallen off me like a cloak: my Co-Masonry,

my priesthood, the teaching about karma, reincarnation,

and the rest of it. I don’t say it isn’t true, I say belief isn’t

knowledge.

But you do follow Krishnaji?

Yes, rather. He looks at us and says: I suppose I have to talk — why do

you come to hear me? — Well, the world is in a mess… Then he paints

a picture of the chaos of modern life. He asks: What is the root of chaos? —

the power of thought! As I sit there I remember Madame Blavatsky saying: The

mind is a great slayer of the Real; let the disciple slay the slayer. Krishnaji puts it in his own way, and then asks

if it’s the mind that creates confusion, how to stop the confusion? Well

— by realizing it, that stops it…then in freedom from confusion

there’s love. That’s his message. It’s so tremendous, we can’t

take it. He’s still emphatic that he’s not a teacher. I don’t

touch his feet — I wanted to, I feel like it. I told him the other day

when I was holding his hand on his historical re-entry into this place that

I feel like touching his feet but I’m not going to. He said: Quite right;

and laughed.

As a last question, what

do you think you have achieved by your seventy-five years association with the

T.S. and Krishnaji?

I am not able to estimate what I have achieved — you or others who meet

me may form their own opinion: I can’t say I have arrived at this or that.

I have learned that nobody can teach me how to meditate or “muditate”,

as most people do. And nobody can tell me how to become spiritual or to define

God. It’s all ineffable wonder and beauty and love. That’s what

I think, I can’t describe it. Should I try, I would destroy it.

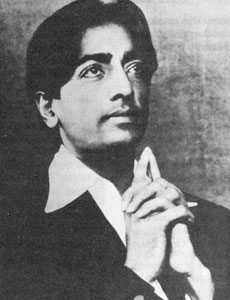

| J. Krishnamurti, a controvertial figure to the end, died 5 years later at the age of 90. |

|

| The young J. Krishnamurti |