1

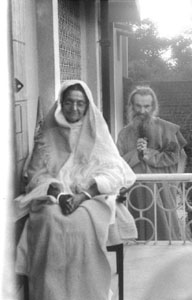

Vijayananda

Sri

Amandamayi Ma Ashram

Kankhal

Hardwar

28th November 1980

Anandamayi Ma is India’s most widely known twentieth centuary woman saint. Her name means the bliss-intoxicated Mother although she has been bliss-intoxicated since childhood -- indeed, she is said to be in an unbroken state of divine consciousness. Her physical beauty in itself has been extraordinary, and although she is now in her middle eighties, much of that beauty remains. Her spiritual magnetism is unchanged. She now rarely sings her bhajans, and never gives formal discourses. It is enough to be in her physical presence and have her silent darshan. She has never been abroad but still travels continuously all over India visiting her many Ashrams.

The day I arrive in her Kankhal Ashram in the Himalayan town of Hardwar, all the arrangements for the three Interviews that follow were wiped out: she decided to give a four-hour silent darshan, something she had not done for years. Devotees are not going to get up and walk away from the presence of their guru to be interviewed by a stranger — they sit and absorb. I also sat and absorbed: there was nothing else for me to do. Perhaps I absorbed too much of her charged radiation because after Ma retired to her room, and we were free to disperse, there was a sort of repulsion at the thought of carrying out my plan to go from Ashram to Ashram, from devotee to devotee asking questions.

I began saying to myself, how can anyone sit in front of one guru after another, absorb, and then expect the devotees to translate the experience into words? Well, the idea behind the Interviews is good, and – yes—it probably hasn’t been done in depth before, but here I am ready to start, but seriously suffering from resented intoxication! You can’t absorb and be expected to ask intelligent questions.

I had prayed to my own guru simply to become a channel for this work. A coward would escape, and right now – but a channel? There is a flash of relief: this is happening on my first day, it’s very late, let’s see what happens tomorrow? If things go on like this, home!

But here comes Ram Alexander my American friend who is one of Ma’s few foreign disciples allowed to live in this Ashram. He is excited: he says Vijayananda is prepared to give his Interview right now. Triumph met by bewilderment – I am still suffering from unexpected intoxication. Ram is unpacking my tape recorder, Vijayananda is waiting, there’s another flash – a happy one -- I can still leave early in the morning!

Vijayananda is being introduced, and I see he is a gentle, elderly Frenchman who speaks softly, rather confidentially, and everything he says is punctuated by much quiet laughter. Yes, yes, he is happy to give his Interview. Even when you’ve absorbed too much and want to escape you have to respond…

Interview 1

Ram Alexander has been kind enough to tell me that you want to know about my background... Well... you see, there are two people: one who died on 2nd February 1951, the other who was born on 2nd February 1951. Now do you want to hear about the dead man or the living man?

Could we try the dead

man first?

The dead man has no great interest — he happened to be a doctor interested

in spirituality. He already had one guru in France where he had been born,

and had practiced meditation for 16 years before coming to India. You see, from

the age of 10 he was rather religious — he was a Jew by birth —

so this boy, instead of playing like other children, was thinking: What is the

nature of God? And it was a big problem and it lasted many years. Finally he

decided that God not being material, the mind or spirit did not exist. So he

became an atheist.

This lasted until he was 17. He was being trained as a rabbi. He had eaten, devoured all Western philosophers but came to the conclusion that religion was a humbug. He was only enthusiastic about Nietzsche.

Now what Nietzsche says is a non-sense, but as a teenager the nonsense he didn’t catch — what he caught was the spirit. Nietzsche is a mystic. Up till then this boy didn’t know what real mysticism was as he was surrounded by bigoted people — you must know them, they have no religious feeling. I was fully disgusted but Nietzsche attracted me just for the mystic flame. Later I found the same flame in the Upanishads without the nonsense, so I became fully Upanishadic. I stick to Vedanta right up to now although my first guru was a Buddhist and he wanted to make a Buddhist out of me.

So that was the dead man’s lovely background. That doctor who practiced in the south of France and whose guru didn’t satisfy him decided in 1950 to come to India.

Thirty years ago hardly anyone travelled to the

East just for spirituality. Did you have to come by boat in those days?

Yes — it was a rarity — very few came for that in those days. The

boat landed in Colombo on 1st January 1951... the first day of the second half

of the century. I actually arrived in India on 15th. I really came to see Ramana

Maharshi — I had not even heard of Anandamayi Ma then. But while preparing

my trip he died. Then I thought: I will go and see Aurobindo! But this fellow

also ran away to nirvana a few days before I took the

boat. As I had arranged everything I said: Well, what is the use? — let

me go!

In Ceylon I stayed in a Buddhist monastery with a German monk: he didn’t inspire me — he was very dry, but really dry. Then I went to Pondicherry, to the Aurobindo Ashram, and saw the Mother. Frankly, I didn’t feel anything. But as it happened, one Canadian lady who had just come from Benares said: If you go there I will give you something to see — the University, the temples, and Anandamayi’s Ashram. I asked: Who is Anandamayi? She said: Oh, she is a lady saint. I asked: She must be old? No, no, she is still fairly young. Then I asked — I didn’t know anything — But there must only be women with her? She replied: There are more men with her than women. So I thought: All right — let me go! But in my imagination I couldn’t help thinking she must be some old humpback. I wanted to go to Rishikesh to see Sivananda, so why not go on and see this lady saint also?

I reached Benares on 1st February 1951 with a letter of introduction to the best man at Ma’s Ashram. But in Benares I had a strange impression I had come home — a strange impression I would never like to leave. Actually I knew I had to leave in three weeks — my return passage was booked. But anyway, I went straight to the fellow with my letter. He was not there. I found his nephew, an amazingly handsome boy, and he was the presiding deity who brought me to Ma.

It was nearing sunset: I didn’t intend to see her — I just thought I would see the Ashram then go away. But as I entered, Ma came out. She looked at me with a strange look — she doesn’t have that look now, slightly up and far away as if she were looking at your destiny, embracing your whole destiny.

Now what struck me first was that she was not a humpback, nor was she old but fairly handsome, although her great beauty did not strike me at that first moment. Her hair was long and flowing, and it surprised me: could a lady saint be that way? I always thought lady saints must be old with odd dress. She was all in white: her simplicity was a shock. Anyhow, I said: Let me stay on — let me see what will happen!

I did not ask for it, but later Ma gave me a private Interview. Atmananda(1) was asked to interpret. Actually, I had nothing to ask: with a saint you don’t ask questions — you want the spiritual contact. But Ma started asking me questions — questions very much to the point. At one stage she said that the German professor who had visited her the day before was a worldly man, but that she could see I was marked as a worshipper of aum. That was the first day. I was supposed to go back to my hotel for dinner, but there was a kirtan and this devotional music was like hearing something from a previous life, a sound I yearned to hear again although I had never heard it before. I was filled with joy just listening to this music and singing.

When I got back to my hotel there was a revolution going on inside me — a real revolution. I was overflowing with happiness, with love: it was something extraordinary. I felt I could not leave Ma. You cannot imagine it. Next day I came back to the Ashram and asked Ma permission to stay there. I moved out of the hotel and spent that first night nearly 30 years ago without blankets on the Ashram floor — there was no bedding. But I was happy. And since that day I have never left Ma.

What happened to your

booked passage?

I just cancelled everything.

You never left India?

I never left. As I used to be a rather cautious type, I asked for a berth on

the next boat — I thought this may turn out to be a passing fancy. But

the next boat left, and the next, and I never used the ticket. I am still here.

When did Ma give you

the orange robes?

First I wore my own Western dress. I didn’t want to put on white as it

gets dirty quickly and I didn’t want to have to keep washing them every

day. Then I started wearing white — not a dhoti but pyjamas. I have a photo taken

with Miguel Serrano(2)

and I look like Charlie Chaplin. In those days I neglected my appearance. The

main reason was that I didn’t want to attract women; when you have this

inner awakening you get a strong attraction power. So for many years I went

rather unkempt, even dirty so as not to attract women

Now I should explain that Ma doesn’t want to give sannyas to Westerners — she doesn’t want to give them orange robes. At least that’s what she says. Now once we were at the Kumbha Mela at Allahabad in 1971. It was the 20th anniversary of my meeting with Ma. She had been wearing this shawl I now have on – it was white then. She gave it to me saying it could be dyed the color I was then wearing – a brownish yellow. I didn’t want to do that; in a kind of joke I said: But gerua(3) would be better. She replied rather sternly: Gerua, no! — you can wear yogya. Then turning to someone she told him to dye the shawl for me. I would have been happy with it staying white, but when we were back in Benares, this person came for the shawl and made it orange, and after 10 years it is still the same colour although it has been washed many times. It wasn’t until Ma’s 80th birthday a few years ago that she gave me these clothes that are all orange. I would never have worn them on my own.

Do you ever practice

as a doctor these days?

Very rarely. There is an Indian doctor here.

Although I can see your

way of life is so Indian, do you ever see yourself back in the West?

Oh, yes — frequently: but my link here is Ma. As long as she is in the

body, I don’t think I will ever go back.

Can you tell me something

about your daily life?

Most of the day I spend in meditation — that’s my job. Just as someone

spends 7 or 8 hours each day in an office, that’s my work. The rest of

the time is spent looking after the body, that’s all. I should tell you,

it is a number of years since I left the Benares Ashram to live here.

Over the years you must

have seen many Westerners in India looking for spiritual upliftment. Some fall

into the hands of imperfect teachers. Can you give any guidelines on how this

can be avoided?

It is very simple. The best way is to have a sincere yearning for God. You don’t

have to run after gurus. You need a pure mind and this

yearning, and everything will be arranged by itself. The guru is not a human being: the guru is all-pervading. So if you want

God in a human form, He will send you the guru — His human form. The guru is more eager to find you than you

are to find him. You are just to open yourself, to purify yourself, to be sincere,

not to look for power — no yearning for power. Then the guru will appear from inside. Those who

don’t find the guru are not ripe, that’s all.

Since you have been with

Ma have you met any other enlightened teachers?

Two are very high in my mind. Swami

Ramdas, who has passed away, and Krishnamurti. Then there is Mother Krishnabai,

who is also very high. Neem Karoli

Baba I had a short meeting with — he impressed me very much, he was

so kind to me. I have written about all this and some of the Ashrams I have

visited in my little book In the Steps of the Yogis.(4)

Can you give a description

of life in this Ashram?

The beauty of Ma’s Ashram is unlike any other. We are free to do what

we like: there is nothing compulsory — I mean free as far as the routine

goes, not as to behaviour. It is unlike other places where you have to get up

at the gong and sit together at fixed times for meals, there’s nothing

like that here.

But I was under the impression

that there are all sorts of rules about the castes not mixing with the Westerners.

That’s different. The rules of behaviour are extremely severe, that I

must say. For example the rule of brahmacharya: everyone is expected to keep

perfect chastity — it is the main rule in Ma’s Ashrams. Then the

food: it is the same — very severe. One must eat pure food. That means

not only meat is prohibited but onions and garlic. It is enough to get kicked

out if one takes even an egg in one’s room.

Is there any significance

in taking a new name?

I didn’t take a new name — it has been given to me by Ma. The significance

is that when you come to the feet of the guru you are born again: it is a second

birth. If Ma does something it has a deep meaning. Ma gave me my name in Ananda

Kashi, a wonderful place in the midst of a jungle 10 miles from Rishikesh with

a few houses built by the Raj Mata of Tehri Garhwal. She received Ma there in

April 1951 just a few weeks after I had come to her. Ma gave 3 names at that

time: she called the place Anand Kashi, the Raj Mata she called Priya, and she

called me Vijayananda.

What is the translation

of your name?

Jaya is victory, Vi is the superlative; Ananda, you must know, means bliss.

Whatever Ma does has a deep meaning — she is a Divine Being.

But if her devotees ask

for a new name will she not give one?

I will give an example to show she does not. There was an American girl wanting

Ma to give her a name ending in ananda

— bliss. Ma looked at me and said: You give her a name! Now the strange

thing is — to show how Ma works — I could give thousands of names,

but my mind became blank like an idiot. Nothing came up — really. Suddenly

in this awful blank one name came up – Mirabai - nothing else. It came

out by itself... I couldn’t say anything else! Ma didn’t want to

give the girl a name herself, but still she was given the name of Mirabai —

Ma didn’t want a name ending in ananda

— perhaps the girl didn’t deserve it. Most important was that Ma

didn’t want to refuse her in case the girl went away feeling she had been

rejected. It appeared that I had found the name, but actually Ma had.

Can you give any other

examples of how Ma relates to and teaches her Western followers?

If you take Ma as a physical body you see only a tiny part. You must see her

as a physical body but being the centre of an all-pervading power. What that

physical body does and what we see is only a small part of what she does. Sometimes

she may be a little distant with Westerners, that I agree. But why do they come?

Why do they sit with her so long? They feel bliss inside. Although she may look

distant outside, inside she gives them happiness. She may have to make a severe

face — perhaps because of these around her who don’t like so many

Westerners coming. But if she is full of love, what is more real?

What is more real?…why should Ma be influenced by some of her close Indian devotees? Can’t they be influenced by what she wants?

It is rather complicated. She herself doesn’t want too many Westerners. She has noticed — she has the insight — that Western civilization is totally different from Indian civilization. And not only the civilization, but the spiritual way of life. Here sexual purity is so important, whereas for Westerners it’s a trifle.

You must take into account that when we talk to anyone there’s an exchange of vibrations, unwillingly perhaps, but it is there. When you and I talk together there is an exchange of minds: you will take something from me, I will take something from you. If you have strong control of mind you will not be influenced by me. But people who don’t have this control will be influenced without their knowledge.

Surely Indian renunciates

would not be influenced?

Most of them are children… they are only sadhus

in name.

But was it so strict

when Ma started her mission?

If you examine the background it’s easier to understand. When she started

– say sixty years ago – she was surrounded by many educated Hindus

who admired the West and Western education. The problem was to bring them back

to their Hindu culture and show them that their traditions, especially their

religious traditions are higher than the Western ones they admired. It was justified.

They were being kicked by the British while continuing to admire them. I know

quite a lot of them although they are now elderly. Ma had to show them: You

are Brahmins, therefore superior men…

you need not worship foreigners. She wanted to give them pride in their religion,

in their nationality, in their higher caste instead of crawling before the

British. This was the atmosphere in India when Ma started.

Even the Brahmins employed by the British were all for the British. They were servile, despising their own religion. The British ridiculed India and Hinduism, and to imitate the British, they put scorn on their own traditions. That was the background in which Ma started. I can tell you very plainly that although I have been here so many years – it’s almost thirty – I have been sometimes put at a disadvantage. I understand her. She still wants to show them that they are not to bow before foreigners… they have a higher civilization… they have a higher religion.

You have been so patient,

I would like to thank you for explaining all that to me.

You know, in the early days when I arrived here many people asked me why I had

decided to leave everything behind — family, friends, country, profession,

wealth — to follow Ma. It is always difficult to reply to such questions,

not because language lacks words but because a word may not have the same meaning

for everyone unless they too have experienced the sensation corresponding to

that word. I have clung to Ma like a shadow all these years, sometimes suffering

torments whenever I am unable to see her. In those early days I couldn’t

even understand what she was saying, but I would spend hours at her feet without

taking my eyes off her.

You see, from the beginning I had the conviction that I was looking at the Lord Himself incarnated in the body of a woman.

|

| A number of books have been written about Vijayananda - some in French by Dr. Jacques Vigne. He has now become a revered venerable teacher himself with his own followers. He did not formally take sannyas although Ma gave him the orange cloth to wear. His entire life has been a model of renunciation – very few sadhus can compete with him on that level. Perhaps in some ways due to his life style, he remains in amazingly good health. At the age of 91 he climbs 3 flights of stairs every day, cooks for himself, and gives satsang to his many devotees for several hours every evening. He has been offered significant positions in the Ashram organization but always declines them. |